Even before COVID-19, working-age Americans struggled to afford healthcare coverage. Now, in the event of an economic downturn, the situation could worsen. Health economist Jane Sarasohn-Kahn explores the findings of the Commonwealth Fund’s latest research.

By Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

Healthcare spending in America is approaching 20% of the nation’s gross domestic product. Would it surprise you to know that $1 in every $5 of household spending in the U.S. also goes toward healthcare in American families?

That is why the Commonwealth Fund’s latest findings from the organization’s 2020 Biennial Health Insurance Survey forecasts a looming crisis in affordability. The report is a wake-up call for the U.S., and particularly for healthcare system stakeholders planning services and finances for 2021 and beyond.

The top line is that, even before the coronavirus pandemic, there has been “persistent vulnerability” among working-age Americans in being able to afford healthcare coverage. In the event of an economic downturn, this situation could worsen.

To set the context for concern, the Commonwealth Fund found that as of March 2020, 2 in 5 working-age people in the U.S. lacked adequate insurance. These were people who were uninsured at the time the survey was conducted in the first quarter of 2020 (12.5% of working-age adults), people who were insured but had a coverage gap in the past year (9.5%), or people insured with high out-of-pocket costs or deductibles relative to income (21.3%).

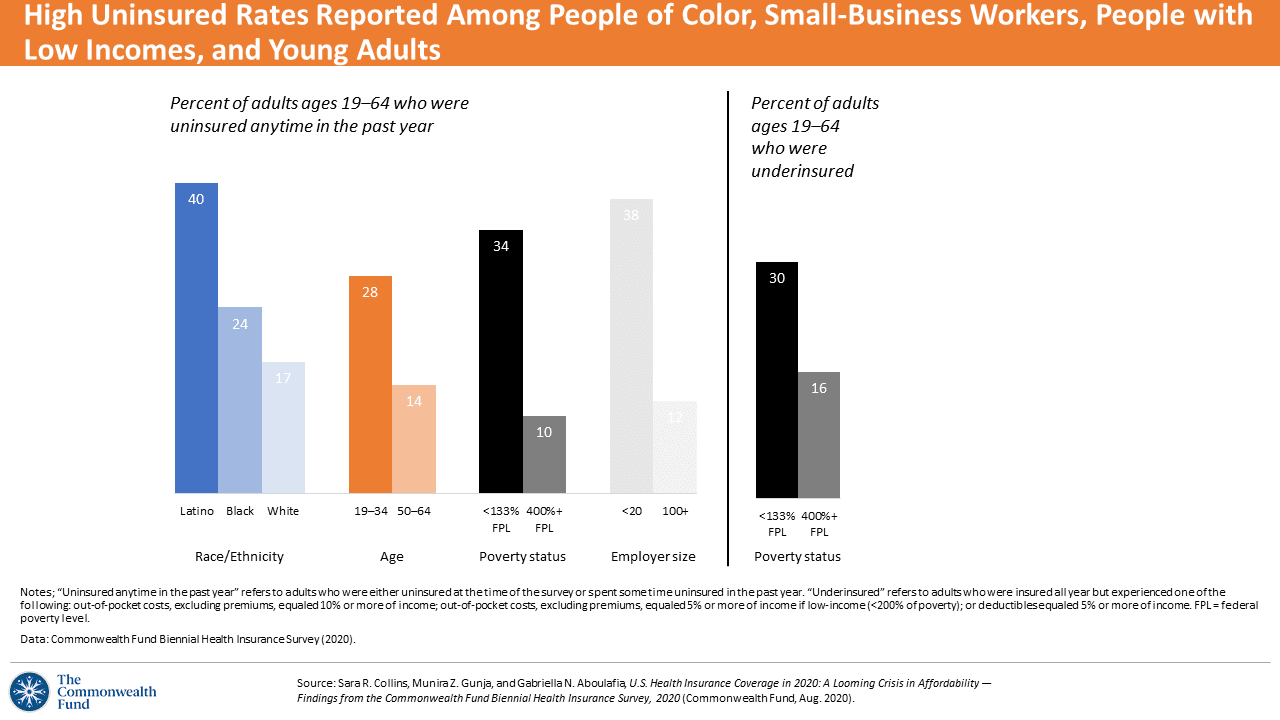

People of color, workers in small businesses, people with lower incomes, and young adults were more likely to have high uninsured rates compared with other working-age adults in the U.S., the first chart illustrates. The uninsured rate for Latino people was over twice as great as that for white adults. For Black people of working age, the uninsured rate was over 40% higher than for white workers.

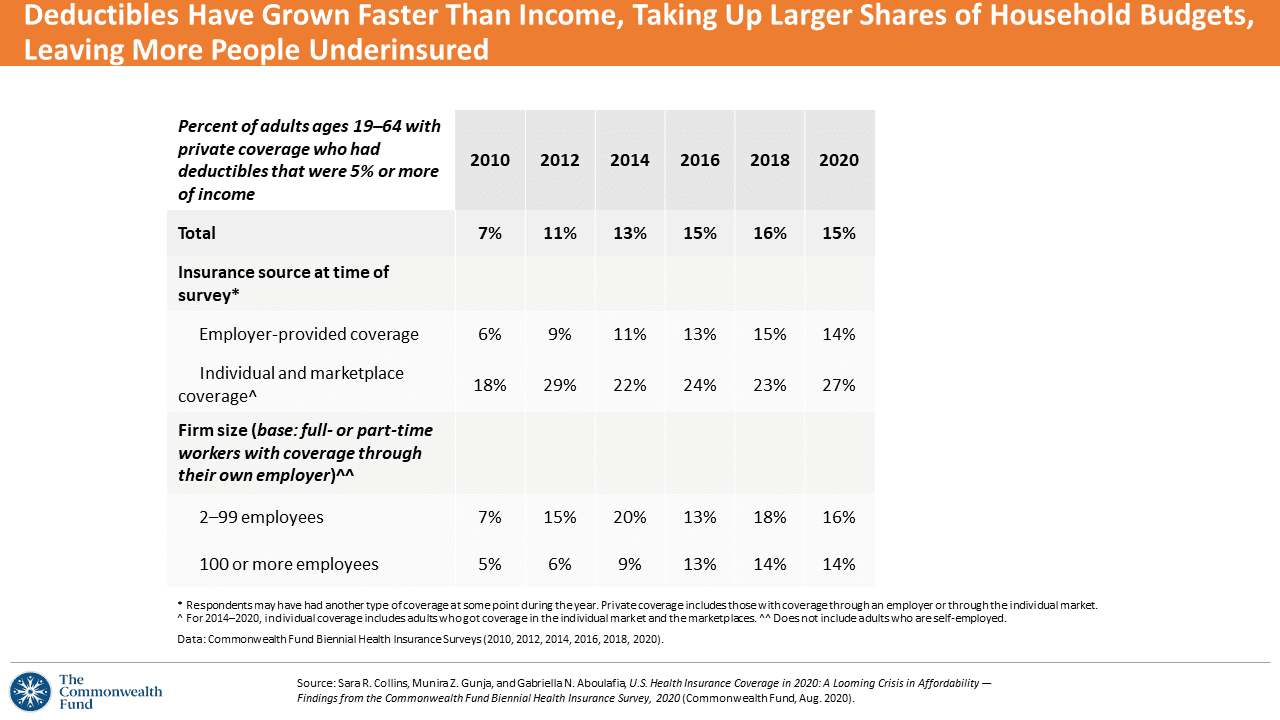

Among people who were insured through private health plans, their share of out-of-pocket costs and the cost of a deductible grew as a share of income.

The proportion of working-age people with deductibles comprising at least 5% of income doubled in 2020 to 15% from 7% in 2010. People purchasing health insurance in individual and Affordable Care Act (ACA) marketplaces faced greater deductibles relative to their incomes than workers in employer-based health plans.

People with higher deductibles more frequently reported financial problems due to medical bills or delaying care because of cost. For insured working people with a deductible of $1,000 or more, 41% had a medical bill problem or took on medical debt, and 42% took on credit card debt due to medical bills. Furthermore, 18% of people with a deductible of $1,000 or greater did not fill a prescription for medications. Overall, 4 in 10 people with private coverage and a deductible of at least $1,000 had at least one of four medical access problems: not filling a prescription; skipping a recommended medical test, treatment or follow-up; having a medical problem but not visiting a doctor or clinic; not seeing a specialist when they needed to do so.

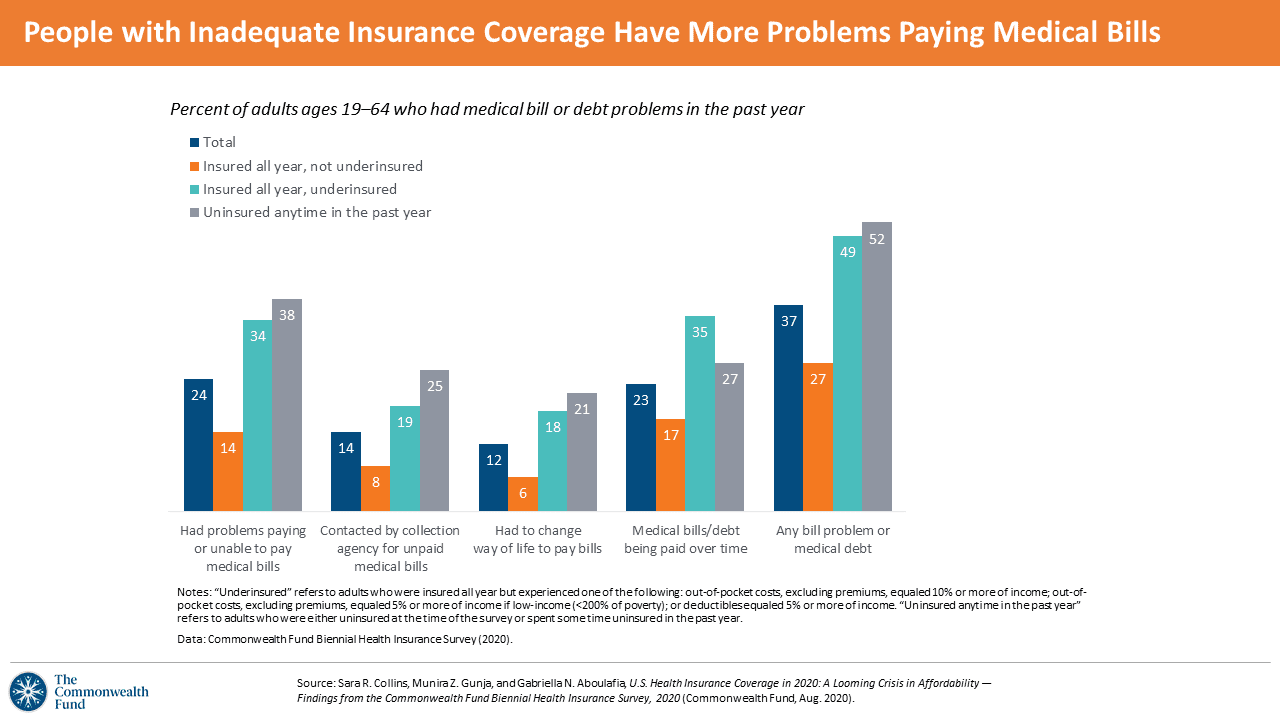

It follows, then, that people who are uninsured or underinsured have more problems paying medical bills. Overall, one-third of working-age Americans had some bill problem or medical debt in the past year; one-half of underinsured or uninsured people had a bill problem, the chart illustrates. Note that 1 in 3 underinsured people—who have some form of health insurance—had medical bill debt they were paying over time (shown in the fourth group of bars in the diagram). Among those paying debt over time, over half had incurred debt of at least $2,000.

Most people who reported medical bill or debt problems said the person in the household incurring the medical bill was insured when care was provided. And across demographics, Black workers with insurance were more likely than whites to report problems with medical bills at rates of 45% versus 35%, the Commonwealth Fund found.

In the U.S., consumers’ financial health is negatively impacted by medical debt. In 2020, 37% of people with medical bill problems in the past two years used all of their savings to deal with the debt; 40% of people received a lower credit rating; 31% took on credit card debt; and 26% were unable to pay for basic needs including food, rent and/or heat.

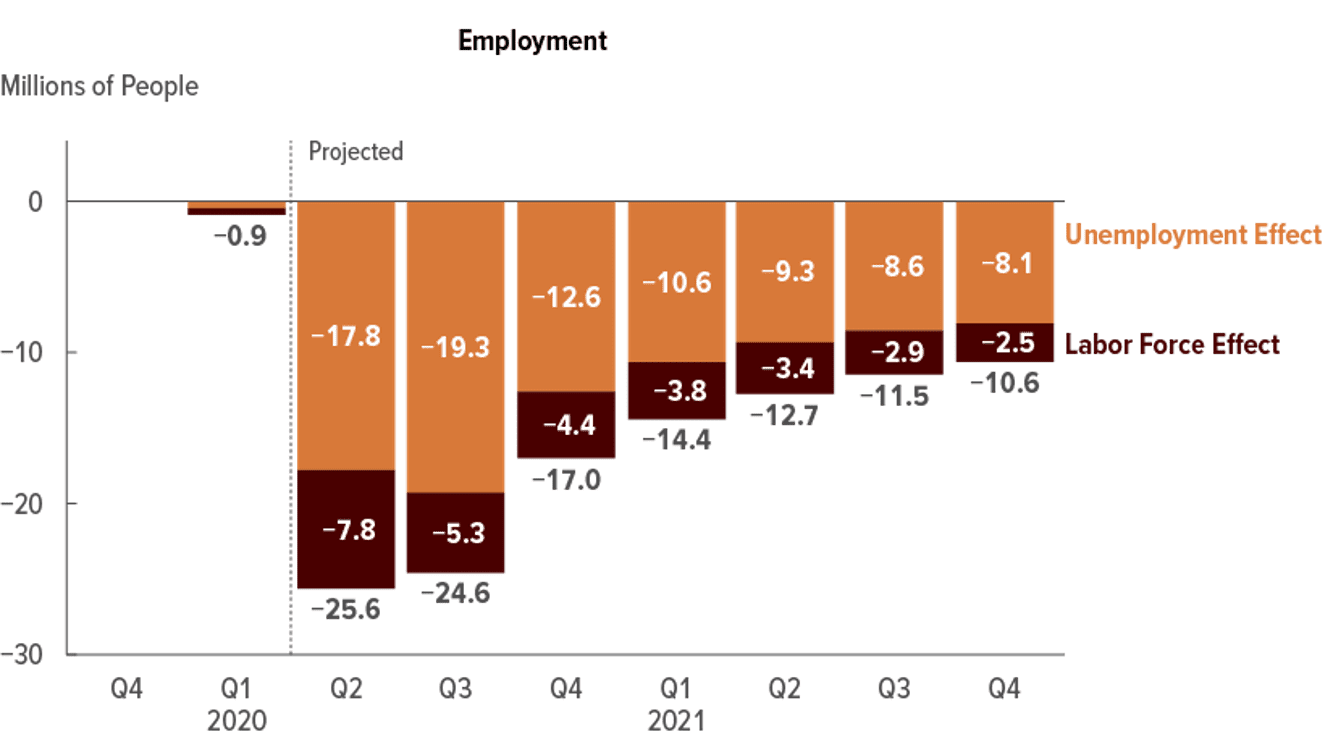

The Commonwealth Fund’s study, conducted at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, found 30 million people uninsured and 40 million people underinsured in the U.S. “These numbers are certain to climb this year,” the Commonwealth Fund concluded in its report, citing the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecast that in the third quarter of 2020, 25 million fewer people will be working in the U.S.

That CBO estimate led The Urban Institute to project that 3.5 million more people in the U.S. would be uninsured by the end of 2020.

As the pandemic persists through 2020 and into winter’s expected flu season, health insecurity in the U.S. would lead to greater numbers of uninsured and underinsured people given both the employment forecast and employers’ continued expansion of high deductibles in the workplace for insured workers and their families.

U.S. healthcare system stakeholders—health plans, physicians, hospitals, pharma and life science companies, health policymakers—should take these statistics into account as they develop business plans for 2021 and beyond. Every healthcare industry segment will feel repercussions in this scenario, where patients as health consumers will be faced with a crisis in healthcare affordability relative to relatively flat incomes.

To address these developments:

- For health plans, consider developing well-designed programs and outreach efforts that ensure members can and do access preventive care and treatment when required. As patients-as-payers postpone necessary care, their self-management of chronic conditions can exacerbate, and outcomes can decline.

- For pharma and life science companies, revisit access programs to ensure patients can fill prescriptions, and ensure maintenance medications for chronic conditions have copayments aligned with value-based programs that drive adherence to therapeutic regimens.

- For hospitals and doctor’s offices, collaborate with patients to provide payment programs that can bolster financial wellness and avoid hits on personal FICO scores.

In the immediate term, for healthcare policymakers at the state level, expanding Medicaid in the 12 states that have not done so would be a basic and important step.

At the federal level, enhancing ACA marketplace subsidies for premiums and cost-sharing would mitigate the self-rationing behavior among underinsured Americans, the Commonwealth Fund recommends.

As in 2018, voters in U.S. elections in 2020 will heavily focus on health and healthcare—with Americans in the midst of dealing with the pandemic in their homes and workplaces, and for the nation in a public health crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed some of the worst aspects of U.S. healthcare, especially related to health disparities and racial justice.

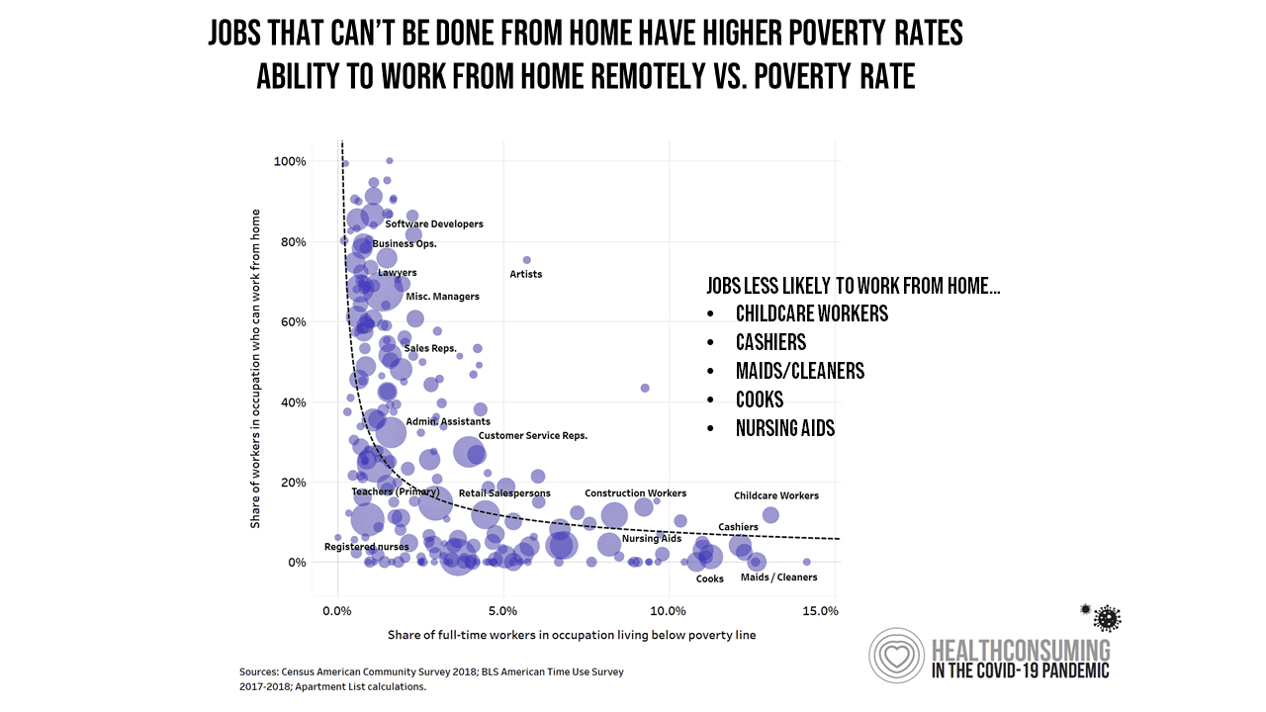

The crisis of affordability diagnosed by the Commonwealth Fund disproportionately hits people of color and those earning lower incomes. In the pandemic, it has also been a fact that lower-income people were largely unable to work from home.

As health insurance in America is tied to the workplace, ensuring that uninsured and underinsured people have affordable access to high-quality healthcare will be on the minds of millions of people adversely impacted in the pandemic. This is a call to action for the healthcare industry to deal with the short-term impacts of the pandemic on people’s access to care. In the longer run, that call to action is to be part of the solution to affordability, access and health equity for all people in America.

Want to hear more from Jane Sarasohn-Kahn? Check out her thoughts on how the pandemic is accelerating the hospital-at-home concept and the sobering statistics on 2020 excess deaths in America.

About The Author: Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

Through the lens of a health economist, Jane defines health broadly, working with organizations at the intersection of consumers, technology, health and healthcare. For over two decades, Jane has advised every industry that touches health including providers, payers, technology, pharmaceutical and life science, consumer goods, food, foundations and public sector.

More posts by Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA