As Americans, we must claim our collective health citizenship, and act on it together.

By Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

As I draft this post, the survival of the Affordable Care Act is at risk, a plethora of people in America don’t trust the Food and Drug Administration, and more than 200,000 Americans have died from the coronavirus,

The COVID-19 pandemic has had side effects well beyond the virus itself. The public health crisis has impacted health across many dimensions: financial health, mental and behavioral health, social health and the overall civic health of the American people.

One gift emerging from the coronavirus is a growing sense in the U.S. that health is made beyond the healthcare system. Health is bolstered, or diminished, everywhere—in the grocery store, in our neighborhoods, in workplaces and, through the pandemic, in our very homes, which have become our safe health hubs.

Health, too, is found at the polling place, in voting for healthcare and health baked into public policy.

I concluded my book published last year, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen, asking this question: “What if people in America were Health Citizens, where the government ensured healthcare as a social and civil right, health informed public policy, and people controlled their health data?”

I concluded my book published last year, HealthConsuming: From Health Consumer to Health Citizen, asking this question: “What if people in America were Health Citizens, where the government ensured healthcare as a social and civil right, health informed public policy, and people controlled their health data?”

This month, my book Health Citizenship: How a Virus Opened Hearts and Minds was published, after an analysis of the first six months of the pandemic’s impact on U.S. consumers and the healthcare system.

This book answers the ultimate question HealthConsuming asked, responding, “If not now [for health citizenship] … then, when?”

The mega-forces reshaping U.S. consumers as parents, children, students, workers, bakers, home cooks and patients—among other personae we are taking on in the crisis—have indeed opened millions of Americans’ hearts and minds as health citizens.

Let us first review the COVID-borne driving forces impacting people living in America; then, we will focus on four pillars of health citizenship unique to America.

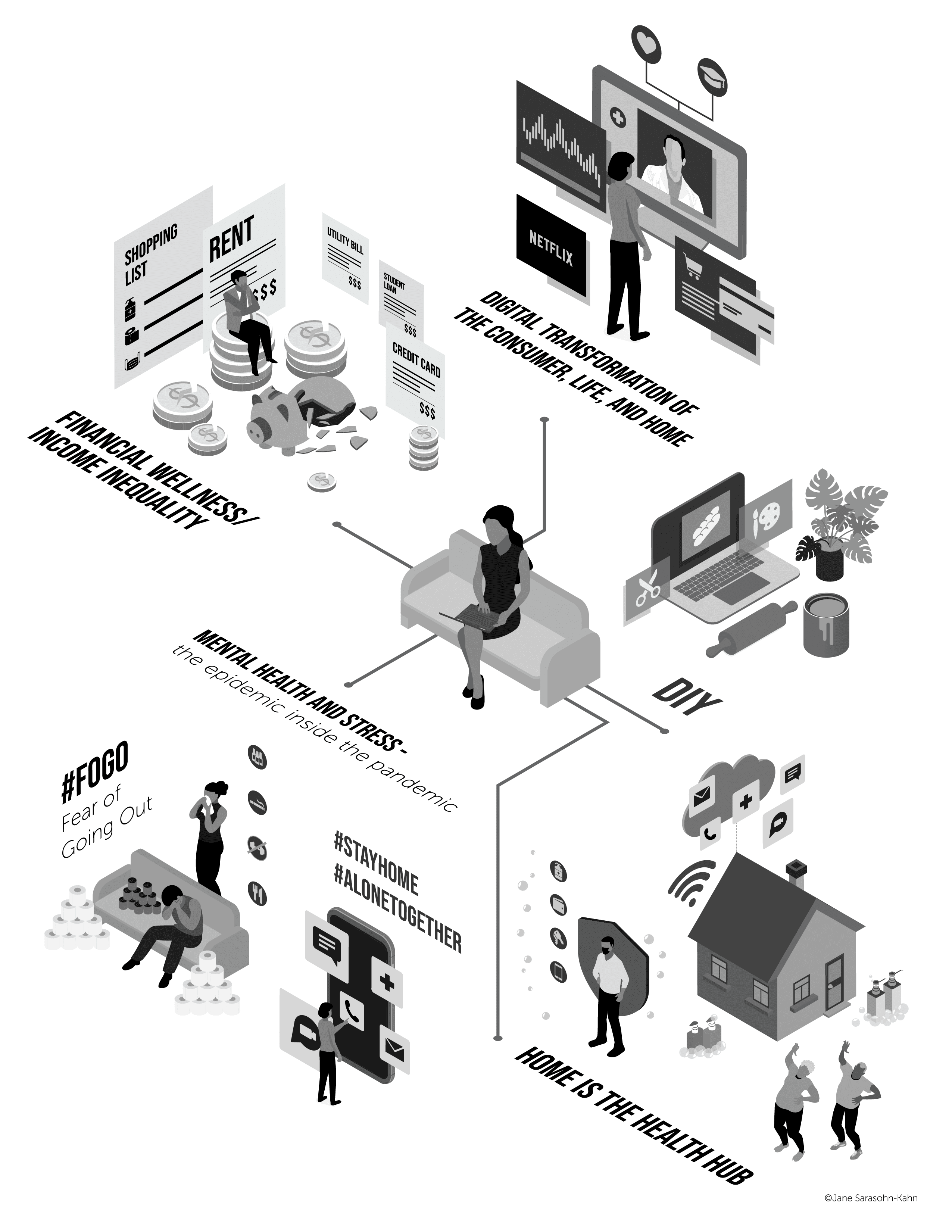

The five transformational consumer impacts of the pandemic have been:

The five transformational consumer impacts of the pandemic have been:

- The digital transformation of the individual

- DIY-everything that could be done for oneself

- Mental and behavioral health stressors

- Financial wellness and growing income inequality

- The home emerging as the health hub

Digital transformation of the individual has happened in the advent of state governors’ mandates to work from home, students’ classrooms shifting from schools and universities to bedrooms and kitchen tables, and WiFi being the new social determinant for safe, connected, daily living.

People’s DIY (“do-it-yourself”) tasks dramatically trended up in the 2008 Great Recession, when Lowe’s and Home Depot grew as retailers for home-fixes and celebrity chefs rose in TV prominence, teaching us how to cook from scratch. In the COVID-19 era, DIY life-flows inspired a kitchen-centered epidemic of baking sourdough bread and home bakers sharing their results in Instagram; home improvements and redecorating, spurring e-commerce sales of furniture and home goods; and gardening as both a home improvement activity and a wellness experience, as explained by this essay, “I Used to Go Out. Now I Go to Home Depot,” a personal recollection of someone in quarantine who felt herself morphing into a “Lawn Dad.”

There is indeed evidence that gardening yields health benefits; in the pandemic, mental health has been profoundly impacted. I addressed this “epidemic beyond the pandemic” in an April 2020 post. That was written early in the pandemic; now, nearly six months later, it is clear the tricky coronavirus will impact our minds, bodies and spirits as much more a public health marathon than a sprint in time.

The financial health impacts have exacerbated a nation already facing income inequality. Millions of employed people who could work from home (WFH) did so, fortunate to hold onto jobs and, with them, health insurance coverage. But millions of other workers have not been able to work virtually. These jobs have largely been in the service sector, garnering lower wages and higher risks for contracting the coronavirus in up-close-and-personal jobs such as childcare workers, home health aides, retail workers and people in the hospitality industry.

Finally, the home has emerged as the consumer’s health hub. As COVID-19 emerged later in the first quarter of 2020, both patients and healthcare providers aligned with the goal of avoiding contracting the virus. Providers canceled elective surgery and other procedures not deemed to be time-critical. Patients canceled healthcare encounters they did not perceive as immediately health-critical to hold the virus at bay. Telehealth quickly filled much of the supply/demand gap between patients and providers. More consumers sought over-the-counter and home-care remedies at grocery stores and pharmacies, which were open for business during people’s self-quarantine. And hospital-to-home programs accelerated during the pandemic, discussed here on the Medecision blog.

Together, these five forces reshaped consumers-as-patients. They also revealed deep fault lines in the American healthcare system, making transparent longtime disparities and inequities that, in the bright light shone by the pandemic, were impossible to look away from.

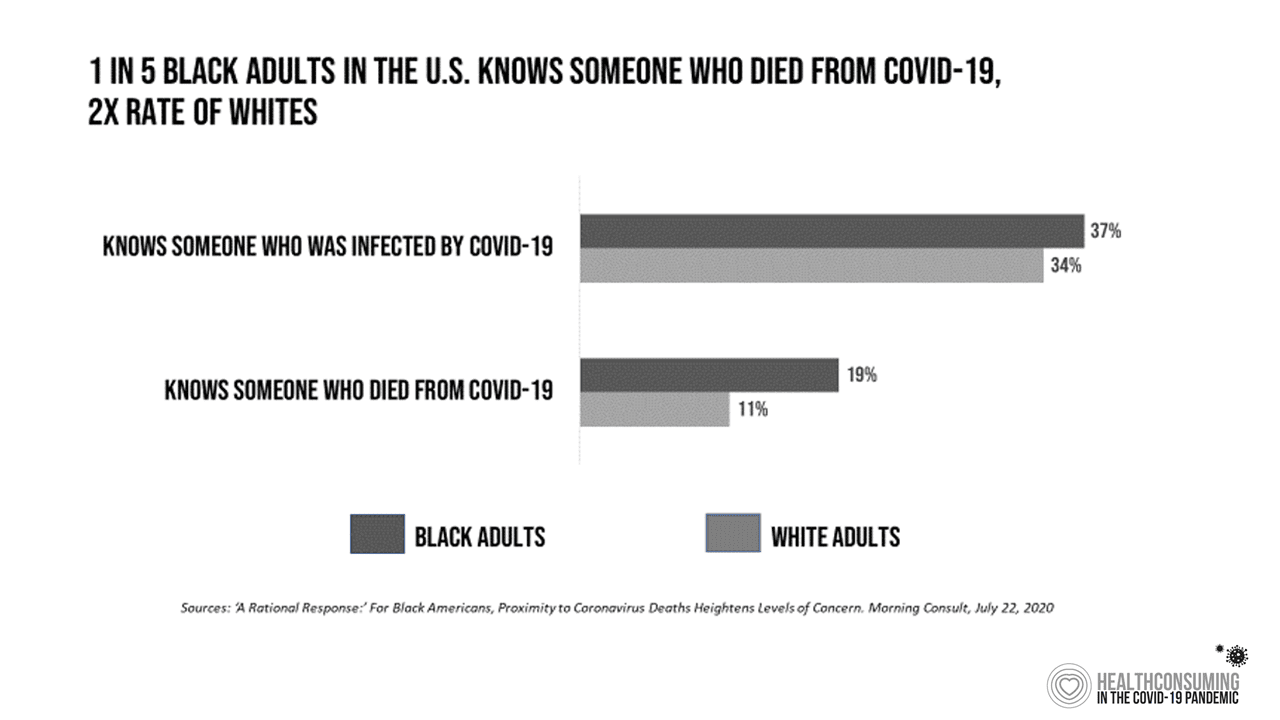

One glaring and tragic data point on health inequity in the age of COVID-19 has been the fact that roughly the same percent of white Americans and Black Americans have known someone infected by the coronavirus. However, nearly twice as many Black people have known someone who died from COVID-19. The crisis showed deep divides of health outcomes for Black and Hispanic people in the U.S. Furthermore, fewer people of color were able to work virtually during the initial work-from-home phase of the pandemic, exacerbating income differentials between richer and poorer Americans.

Food insecurity, too, exacerbated during the pandemic. And while more white Americans queued up in long community food pantry lines for food access, people’s risk for this social determinant, too, was more acutely felt by Black and Hispanic people in the U.S.

COVID-19 has been a wake-up call for Americans to claim their health citizenship.

The Milken Institute defines the concept as “a set of rights and responsibilities for both the individual and the state—a social contract.” The goals of #HealthCitizenship, Milken Institute describes, are to increase public engagement in biomedical innovation and healthcare; to advocate for the individual’s rights within this engagement; and to establish the responsibilities of institutions including but not limited to healthcare providers, researchers, biopharmaceutical companies and health insurers, among many other stakeholders.

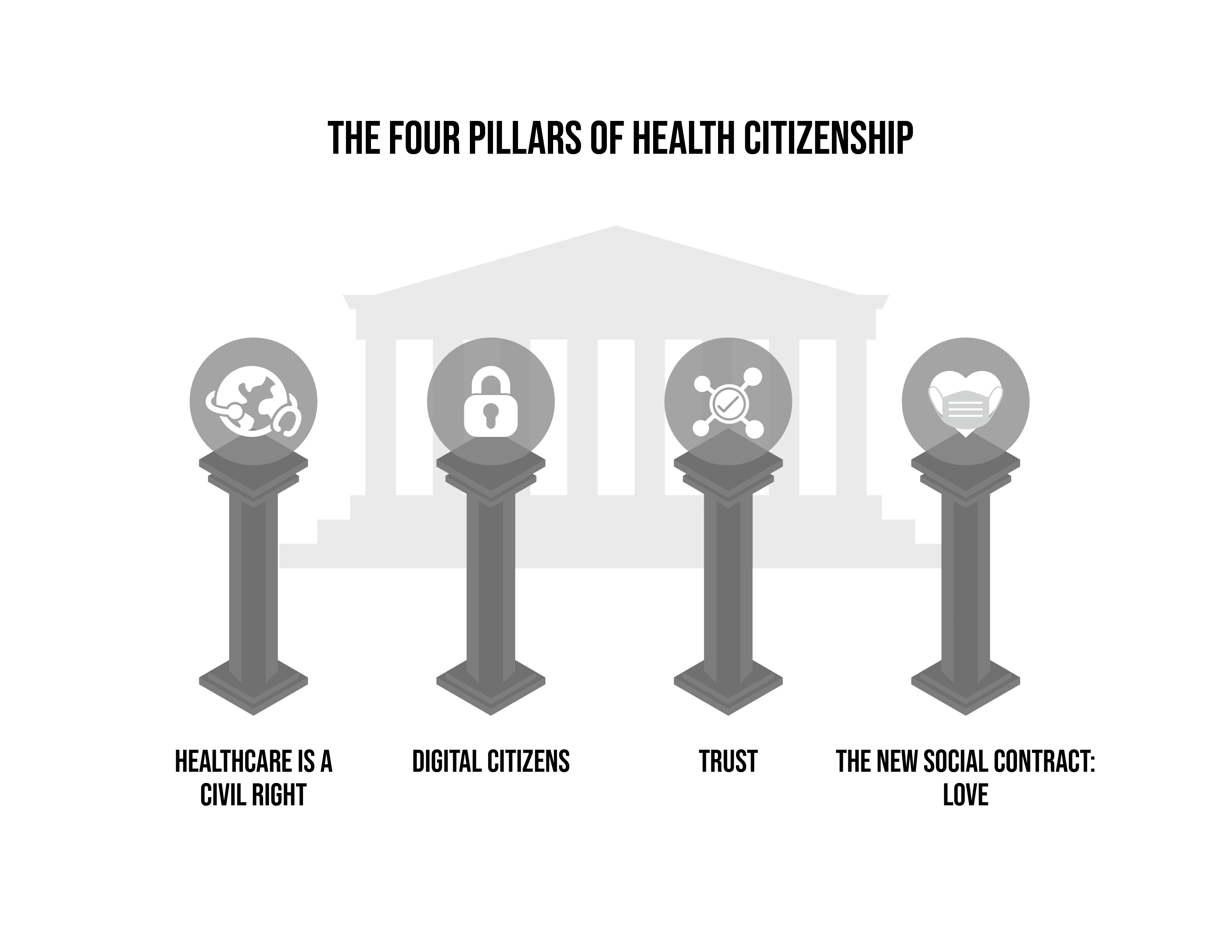

In light of what we have learned through the coronavirus pandemic, I am reframing health citizenship in a broader context, calling out four pillars of health citizenship:

In light of what we have learned through the coronavirus pandemic, I am reframing health citizenship in a broader context, calling out four pillars of health citizenship:

- Healthcare as a civil right for all

- Digital citizenship, which is underpinned by a comprehensive privacy law that covers all personal data

- Trust, in science and between each other

- A new social contract, which is love—exemplified in the COVID-19 era by wearing a mask

Why these four pillars? Because:

- Lack of healthcare access has caused people in the U.S. to self-ration care because of cost, avoiding medical treatment even when people felt symptoms of the coronavirus.

- HIPAA does not cover information flows that are not part of business associate agreements; we know that in a public health crisis, our wearable technologies, smartphones and other digital health apps that generate data about us can be useful for contact tracking, tracing, and forecasting emerging hot spots of the virus. But data flows from consumer-generated devices often fall outside of HIPAA protections. Most Americans have in fact not trusted sharing personal data with either government agencies or “Big Tech.”

- Trust in institutions was eroding before the pandemic; in the crisis, our trust in science, institutions and government has further declined, compromising our ability as a nation to crush the pandemic the way health citizens in other countries have done in concert with their leadership.

- That social contract of “love” means that I wear the mask for you, and you for me.

A report from the Brookings Institution published this month discusses A New Contract With the Middle Class. In this report, authors Richard V. Reeves and Isabel V. Sawhill, both senior fellows at Brookings, assert that “since our nation’s founding, the American Dream has always been based on an implicit understanding—a contract if you will—between individuals willing to work and contribute, and a society willing to support those in need and to break down the barriers in front of them.”

A report from the Brookings Institution published this month discusses A New Contract With the Middle Class. In this report, authors Richard V. Reeves and Isabel V. Sawhill, both senior fellows at Brookings, assert that “since our nation’s founding, the American Dream has always been based on an implicit understanding—a contract if you will—between individuals willing to work and contribute, and a society willing to support those in need and to break down the barriers in front of them.”

We are in this moment of barrier-breaking, a new road where we drive toward partnership, prevention and pluralism. Health cannot be separated from the rest of our lives, Brookings believes. We were relatively unwell before COVID-19, suffering deaths of despair due to accidents, overdoses and suicide. Americans have been underserved by mental health resources, which are in short supply in much of the nation. The prevalence of diabetes continues to rise, and public policy addressing food and nutrition bolsters poor health, particularly in school-age Americans.

Health plans, hospitals and health systems, biopharmaceutical companies and digital health innovators all play a role in helping move the U.S. toward health citizenship. All healthcare industry segments can partner and collaborate for health and addressing the risks of social determinants that detract from health, prevent illness and promote wellness, and provide inclusive workplaces that welcome diverse and creative thinking.

Can we summon the courage to claim and act on, together, our collective health citizenship?

We must.

About The Author: Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

Through the lens of a health economist, Jane defines health broadly, working with organizations at the intersection of consumers, technology, health and healthcare. For over two decades, Jane has advised every industry that touches health including providers, payers, technology, pharmaceutical and life science, consumer goods, food, foundations and public sector.

More posts by Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA