Telehealth usage skyrocketed during COVID-19. But it also revealed inequities in the healthcare system.

By Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

In March, the World Health Organization (WHO) used the word “pandemic” to describe the worldwide coronavirus crisis, and U.S. healthcare providers began using telehealth services to try to protect frontline healthcare workers and prevent patients from spreading the virus.

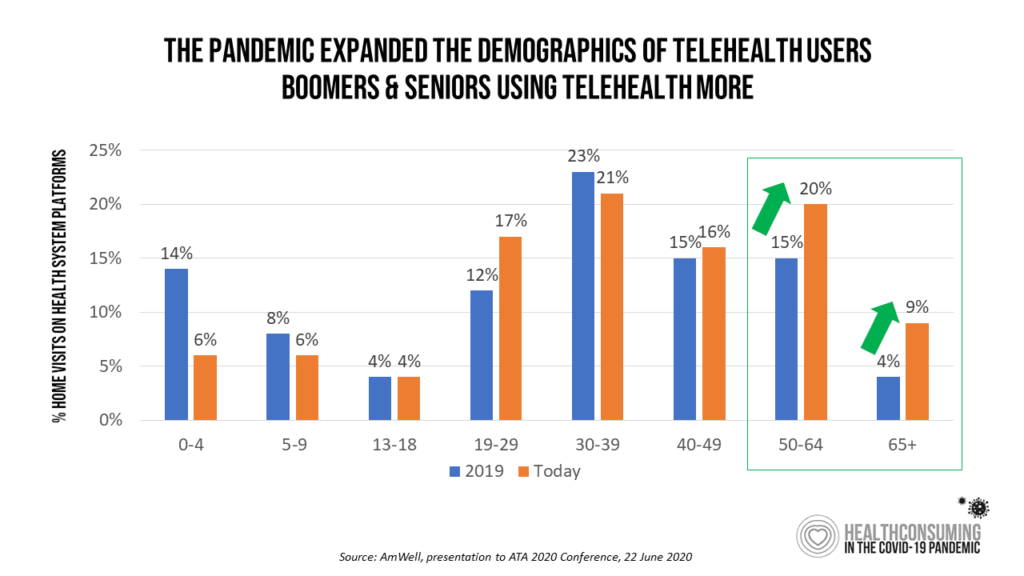

That’s what Amwell, a telemedicine provider, experienced. On the first day of this week’s all-virtual annual conference of the American Telemedicine Association (ATA), Amwell reported significant growth in telehealth usage.

This Amwell data illustrated that older people have taken advantage of virtual care platforms during the pandemic, rebalancing the demographic profile of just who is benefiting from telehealth.

The pandemic ushered in hockey-stick growth for virtual care, a phenomenon universally experienced from Wuhan, China, to Lombardy, Italy, to New York City and throughout the United States.

But what will it take to not just “carpe diem,” but “carpe momentum”—seize the momentum that COVID-19 has gifted healthcare in America in 2020?

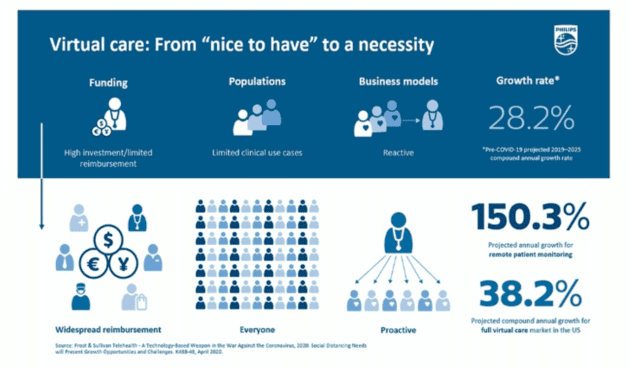

In their ATA session, “Defining the New American Home: Healthy Living through Telehealth from Hospital to Home,” a team from Philips noted that virtual care shifted from a “nice to have” service to a necessity, an essential access point for healthcare. The pandemic forced a grand alignment of risk management for healthcare providers and patients because:

- Patients were wary of exposing themselves to the virus in both hospitals and doctor’s offices; and, at the same time,

- Providers wanted to ensure their front-line workers—physicians, nurses, allied health professionals alike—would be protected as much as possible from further exposure to the highly infectious virus.

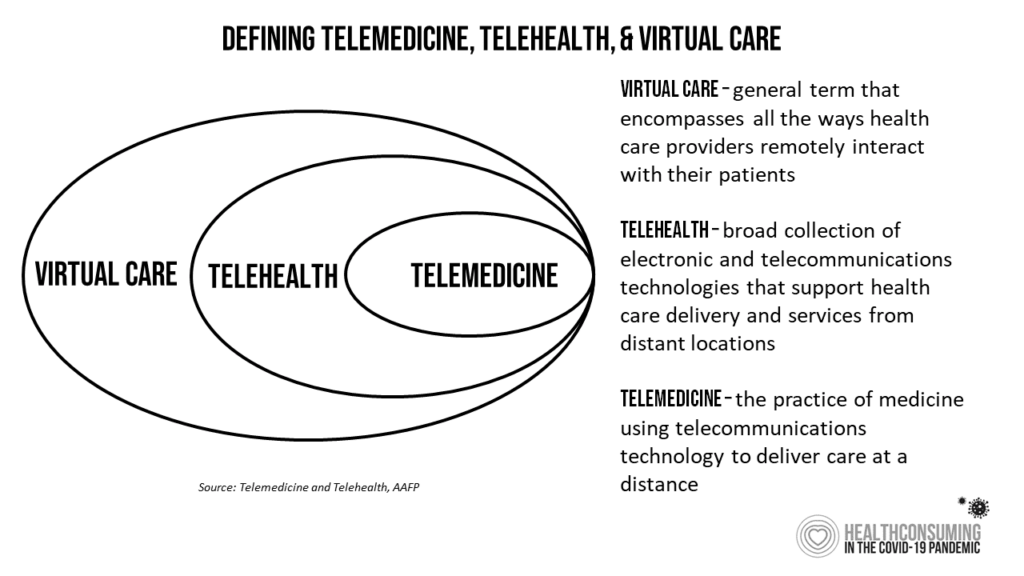

Enter the coronavirus and fast adoption of telecare. The American Association of Family Practice developed this construct to help us differentiate among telemedicine, telehealth and virtual care.

By mid-March 2020, healthcare providers stood up a variety of virtual care programs, enabled through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and other healthcare agencies’ relaxation of various rules and regulations that have long prevented the mass distribution and adoption of telemedicine. These included:

- Changes to Medicare, announced by the CMS on March 17, extending telehealth coverage of more than 80 services such as home visits, emergency department visits and nursing facility visits to be covered with payment parity.

- Use of videoconferencing via smartphone and talk-only calls to be covered for payment, with temporary changes to HIPAA allowing use of apps that lacked cybersecurity benchmarks; these included Apple FaceTime, Facebook Messenger, Google Hangouts, Skype and Zoom, among others.

- The eligibility of Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) and rural health clinics to provide virtual care.

- Medicaid expanding telehealth coverage in all 50 states and Washington, D.C., to reimburse for live videoconferencing between patients and doctors enrolled in the program.

- Commercial insurers covering telehealth, some waiving out-of-pocket costs for plan members using telehealth, and reimbursing virtual care when patients consulted with out-of-network physicians.

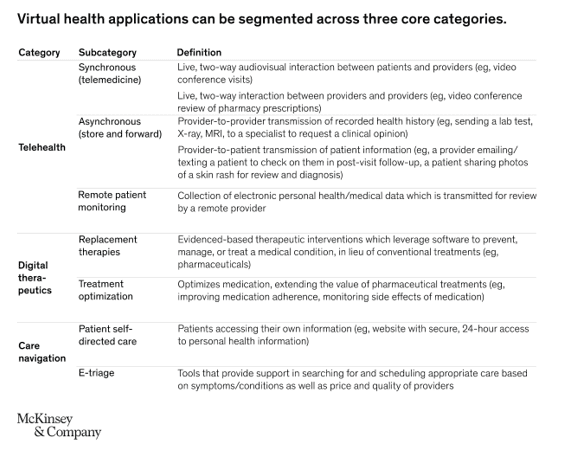

McKinsey looked into the future of virtual health care during the pandemic, segmenting the service types into categories: synchronous, real-time telemedicine; asynchronous, store-and-forward telehealth; telehealth including remote patient monitoring and software and apps to replace traditional therapies; digital therapeutics, using software-as-medicine; care navigation, with tools for patients to self-care at home; and e-triage tools, enabling patients to seek and schedule appointments, access cost information and self-diagnose symptoms.

During the pandemic, the most commonly used form of virtual care was synchronous telemedicine. Looking forward five to 10 years, McKinsey projected that most providers will invest in all forms of care across this landscape.

Delivering care during the pandemic, providers have been brave, bullish and justifiably proud of utilizing telehealth in a matter of weeks compared with what many analysts expected to happen over many years.

But a pandemic, as long as it may feel to us emotionally, physically and fiscally, does not a long-term market make. There remain concerns and barriers that we in the healthcare industry, across our silos and segments, must wrestle and resolve. Among these obstacles are equity and access across all patients, connectivity, privacy and trust, and the political will to make these things happen and scale.

COVID-19 Revealed the Inequities in U.S. Healthcare

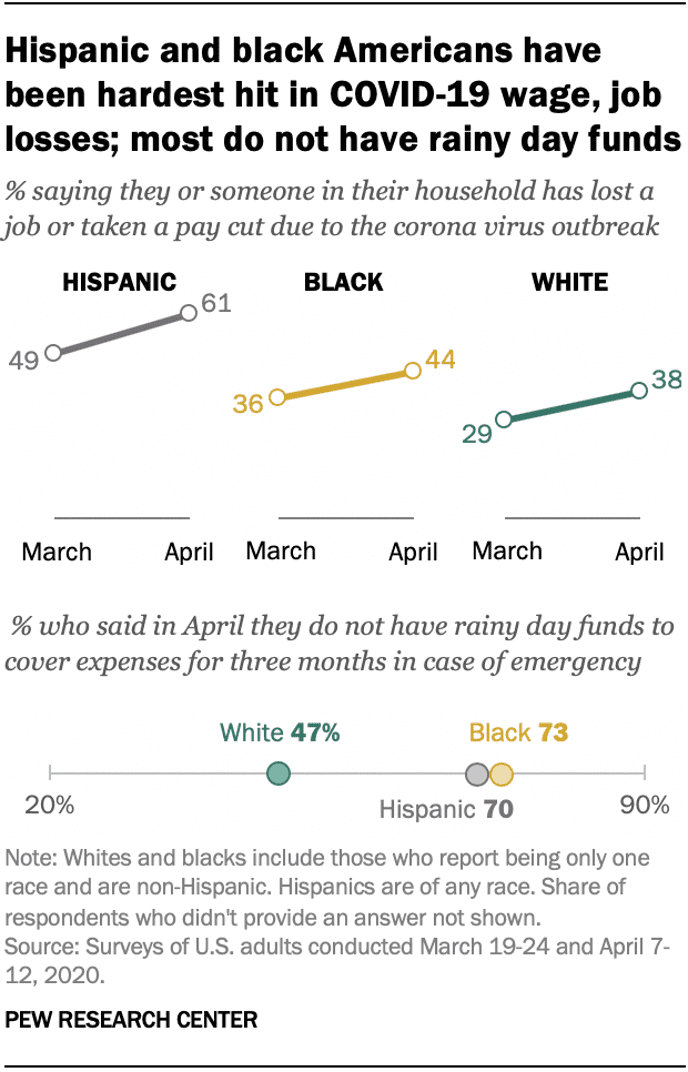

There has been the mass crisis of COVID-19 for the U.S. nationally, and the disproportionate impact on people of color and those who earn lower incomes—often, those workers on whom quarantined Americans depend for trucking food across the country, stocking grocery store shelves and staffing crowded e-commerce distribution centers.

The pandemic was not the origin story for health disparities in America, but more of a magnifying mirror on the long-term challenge of inequity in U.S. healthcare. Underneath the higher mortality and infection rates for COVID-19 in Black and Latinx communities are the social determinants of health that have long plagued patient outcomes in the U.S.

Just layering virtual care technology on top of a healthcare system underpinned by food insecurity, lack of transportation, unsafe housing, dirty water and air, and dramatic income inequality will do little to address the COVID-19 disparities that have hit Black and Hispanic communities and patients so hard.

COVID-19 Revealed the Inequities in U.S. Digital Access

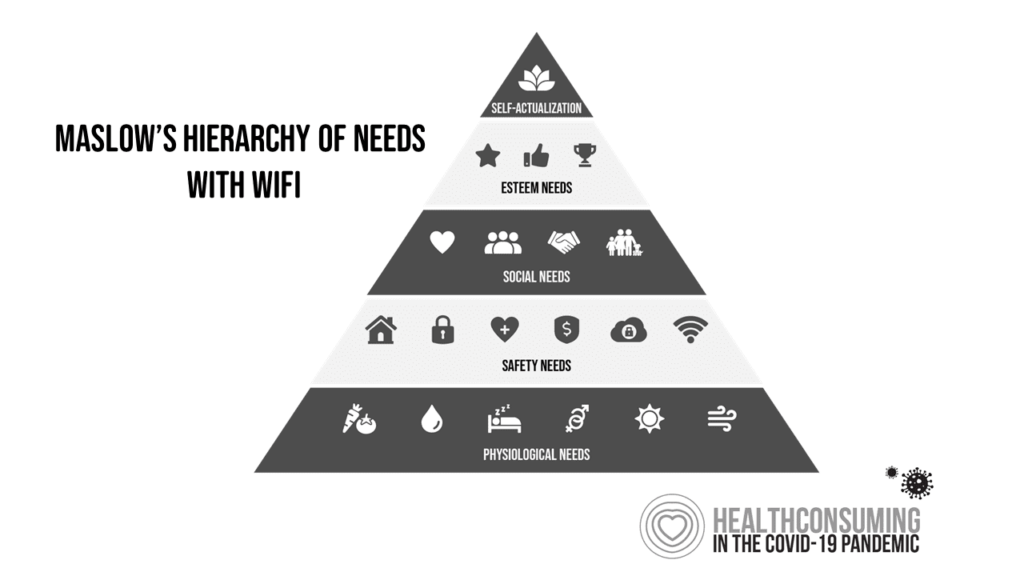

Another disparity has been revealed and accentuated by the pandemic: lack of access to broadband connectivity and hardware to enable people to get connected to the internet. Wi-Fi has become a basic social determinant of health and modern living for work, for education and for medical care access. Many of the students who were forced to be home-schooled during shelter-in-place mandates lacked connectivity to their schools and teachers; some families needed financial and technical support to gain access to broadband and/or tablets, smartphones, or PCs for home use. The pandemic has shown that, in America, we are “unequally disconnected,” in the words of The Brookings Institution.

Telehealth payment, too, was limited in the pandemic to only certain kinds of transactions that used smartphones. Yet many patients, and particularly those with lower incomes, may have been using texting phones. Texting has been shown to be an immensely powerful communications channel for many patient-doctor interactions. Payment parity in virtual care must consider the continuum of patient-owned technology, meeting people where and how they live, work, play and communicate.

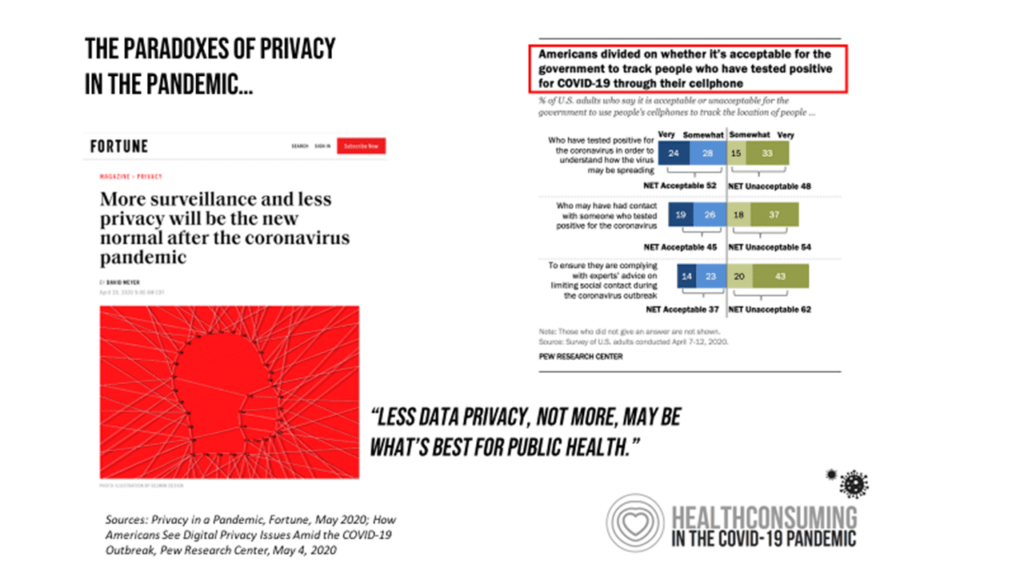

The Dual Edge of Privacy in the U.S.

Privacy aspects during a public health crisis are often “softened” to bolster access to people’s personal health information for the benefit of the collective. This is a double-edged sword: The graphic contrasts an article from Fortune magazine, noting, “Less data privacy, not more, may be what’s best for public health.”

Contrast that ethos with data from the Pew Research Center on the right side of the graphic, where a Pew Research Center poll found that U.S. adults were divided on whether they would be open to sharing their data with government agencies tracking COVID-19 through their mobile phones.

As a real-life example of this conundrum, coronavirus contact tracing got off to a “bumpy start” in New York City, The New York Times reported. Many people infected with the virus were worried about sharing their data with tracers.

Political Will for Telehealth and Healthcare Access After COVID-19

In mid-June, the U.S. Senate HELP Committee held a hearing to be updated on U.S. healthcare providers’ learnings about telehealth in the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Joseph Kvedar, president of the ATA, testified and said:

“I have seen firsthand the many ways telehealth bridges the gap between a critical provider shortage and a growing patient population—a problem that existed prior to the pandemic, and one that will only worsen. However, we need Congress’s support to ensure patients and providers do not go over the telehealth ‘cliff’ as our nation eventually emerges from the pandemic. We must make sure that essential telehealth services do not abruptly end with the public health emergency, especially as we look to reorient our healthcare system to deliver 21st-century care.”

America’s frontline healthcare workers and hospital systems have collaborated in the pandemic to provide care, up-close-and-personal, in COVID-19 units and ICUs, in long-term care facilities and in peoples’ homes, to deliver care under the most challenging circumstances imaginable. There’s very little healthcare providers can do, though, to scale social determinants of health like nutrition and clean water in a town, or to provide broadband to the last mile and city or rural block, to rectify dramatic income inequality in certain ZIP codes, or to bolster literacy to people living in a particular neighborhood.

That takes political will. It is time to carpe momentum not only for telehealth, but for health equity, onto which the pandemic has shined a bright, if sobering, light.

About The Author: Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA

Through the lens of a health economist, Jane defines health broadly, working with organizations at the intersection of consumers, technology, health and healthcare. For over two decades, Jane has advised every industry that touches health including providers, payers, technology, pharmaceutical and life science, consumer goods, food, foundations and public sector.

More posts by Jane Sarasohn-Kahn, MA, MHSA